Home :: Ancient World Wonders :: Chichen Itza

Chichen Itza

Chichen Itza was a large pre-Columbian city built by the Maya civilization. The archaeological site is located in the municipality of Tinum, in the Mexican state of Yucatán.

Chichen Itza was one of the largest Maya cities and it was likely to have been one of the mythical great cities, or Tollans, referred to in later Mesoamerican literature. The city may have had the most diverse population in the Maya world, a factor that could have contributed to the variety of architectural styles at the site.

The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Institute of Anthropology and History). The land under the monuments had been privately owned until 29 March 2010, when it was purchased by the state of Yucatán. Chichen Itza is one of the most visited archaeological sites in Mexico; an estimated 1.2 million tourists visit the ruins every year.

Machu Picchu is vulnerable to threats from a variety of sources. While natural phenomena like earthquakes and weather systems can play havoc with access, the site also suffers from the pressures of too many tourists. In addition, preservation of the area's cultural and archaeological heritage is an ongoing concern. Most notably, the removal of cultural artifacts by the Bingham expeditions in the early 20th century gave rise to a long-term dispute between the government of Peru and the custodian of the artifacts, Yale University.

History : The layout of Chichen Itza site core developed during its earlier phase of occupation, between 750 and 900 AD. Its final layout was developed after 900 AD, and the 10th century saw the rise of the city as a regional capital controlling the area from central Yucatán to the north coast, with its power extending down the east and west coasts of the peninsula. The earliest hieroglyphic date discovered at Chichen Itza is equivalent to 832 AD, while the last known date was recorded in the Osario temple in 998.

Establishment The Late Classic city was centred upon the area to the southwest of the Xtoloc cenote, with the main architecture represented by the substructures now underlying the Las Monjas and Observatorio and the basal platform upon which they were built.

Ascendancy Chichen Itza rose to regional prominence towards the end of the Early Classic period (roughly 600 AD). It was, however, towards the end of the Late Classic and into the early part of the Terminal Classic that the site became a major regional capital, centralizing and dominating political, sociocultural, economic, and ideological life in the northern Maya lowlands. The ascension of Chichen Itza roughly correlates with the decline and fragmentation of the major centers of the southern Maya lowlands.

As Chichen Itza rose to prominence, the cities of Yaxuna (to the south) and Coba (to the east) were suffering decline. These two cities had been mutual allies, with Yaxuna dependent upon Coba. At some point in the 10th century Coba lost a significant portion of its territory, isolating Yaxuna, and Chichen Itza may have directly contributed to the collapse of both cities.

Site Description:

Chichen Itza was one of the largest Maya cities, with the relatively densely clustered architecture of the site core covering an area of at least 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi). Smaller scale residential architecture extends for an unknown distance beyond this. The city was built upon broken terrain, which was artificially levelled in order to build the major architectural groups, with the greatest effort being expended in the levelling of the areas for the Castillo pyramid, and the Las Monjas, Osario and Main Southwest groups. The site contains many fine stone buildings in various states of preservation, and many have been restored. The buildings were connected by a dense network of paved causeways, called sacbeob. Archaeologists have identified over 80 sacbeob criss-crossing the site, and extending in all directions from the city.

The architecture encompasses a number of styles, including the Puuc and Chenes styles of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The buildings of Chichen Itza are grouped in a series of architectonic sets, and each set was at one time separated from the other by a series of low walls. The three best known of these complexes are the Great North Platform, which includes the monuments of El Castillo, Temple of Warriors and the Great Ball Court; The Osario Group, which includes the pyramid of the same name as well as the Temple of Xtoloc; and the Central Group, which includes the Caracol, Las Monjas, and Akab Dzib.

South of Las Monjas, in an area known as Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén) and only open to archaeologists, are several other complexes, such as the Group of the Initial Series, Group of the Lintels, and Group of the Old Castle.

Architectural groups :

Great North Platform

El Castillo

Dominating the North Platform of Chichen Itza is the Temple of Kukulkan (a Maya feathered serpent deity similar to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl), usually referred to as El Castillo ("the castle"). This step pyramid stands about 30 metres (98 ft) high and consists of a series of nine square terraces, each approximately 2.57 metres (8.4 ft) high, with a 6-metre (20 ft) high temple upon the summit. The sides of the pyramid are approximately 55.3 metres (181 ft) at the base and rise at an angle of 53°, although that varies slightly for each side. The four faces of the pyramid have protruding stairways that rise at an angle of 45°. The talud walls of each terrace slant at an angle of between 72° and 74°. At the base of the balustrades of the northeastern staircase are carved heads of a serpent.

Mesoamerican cultures periodically superimposed larger structures over older ones, and El Castillo is one such example. In the mid-1930s, the Mexican government sponsored an excavation of El Castillo. After several false starts, they discovered a staircase under the north side of the pyramid. By digging from the top, they found another temple buried below the current one. Inside the temple chamber was a Chac Mool statue and a throne in the shape of Jaguar, painted red and with spots made of inlaid jade. The Mexican government excavated a tunnel from the base of the north staircase, up the earlier pyramid’s stairway to the hidden temple, and opened it to tourists. In 2006, INAH closed the throne room to the public.

On the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, in the late afternoon, the northwest corner of the pyramid casts a series of triangular shadows against the western balustrade on the north side that evokes the appearance of a serpent wriggling down the staircase, which some scholars have suggested is a representation of the feathered-serpent god Kukulkan.

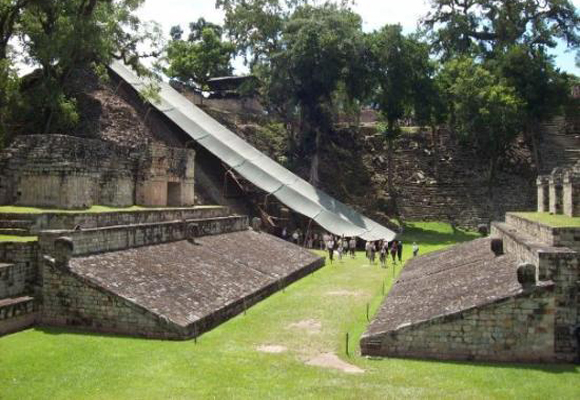

Great Ball Court

Archaeologists have identified thirteen ballcourts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame in Chichen Itza, but the Great Ball Court about 150 metres (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is by far the most impressive. It is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica. It measures 168 by 70 metres (551 by 230 ft). The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 metres (312 ft) long. The walls of these platforms stand 8 metres (26 ft) high; et high up in the centre of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents.

At the base of the high interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players. In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound emits streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado). This small masonry building has detailed bas relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure that has carving under his chin that resembles facial hair. At the south end is another, much bigger temple, but in ruins.

Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar. The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two, large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. Inside there is a large mural, much destroyed, which depicts a battle scene.

In the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar, which opens behind the ball court, is another Jaguar throne, similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo, except that it is well worn and missing paint or other decoration. The outer columns and the walls inside the temple are covered with elaborate bas-relief carvings.

The tzompantli or Skull Platform

The Tzompantli, or Skull Platform (Plataforma de los Cráneos), shows the clear cultural influence of the central Mexican Plateau. Unlike the tzompantli of the highlands, however, the skulls were impaled vertically rather than horizontally as at Tenochtitlan.

The Platform of the Eagles and the Jaguars (Plataforma de Águilas y Jaguares) is immediately to the east of the Great Ballcourt. It is built in a combination Maya and Toltec styles, with a staircase ascending each of its four sides. The sides are decorated with panels depicting eagles and jaguars consuming human hearts.

This Platform of Venus is dedicated to the planet Venus. In its interior archaeologists discovered a collection of large cones carved out of stone, the purpose of which is unknown. This platform is located north of El Castillo, between it and the Cenote Sagrado.

The Temple of the Tables is the northernmost of a series of buildings to the east of El Castillo. Its name comes from a series of altars at the top of the structure that are supported by small carved figures of men with upraised arms, called “atlantes.”

The Steam Bath is a unique building with three parts: a waiting gallery, a water bath, and a steam chamber that operated by means of heated stones.

Sacbe Number One is a causeway that leads to the Cenote Sagrado, is the largest and most elaborate at Chichen Itza. This “white road” is 270 metres (890 ft) long with an average width of 9 metres (30 ft). It begins at a low wall a few metres from the Platform of Venus. According to archaeologists there once was an extensive building with columns at the beginning of the road.

Cenote Sagrado

The Yucatán Peninsula is a limestone plain, with no rivers or streams. The region is pockmarked with natural sinkholes, called cenotes, which expose the water table to the surface. One of the most impressive of these is the Cenote Sagrado, which is 60 metres (200 ft) in diameter, and sheer cliffs that drop to the water table some 27 metres (89 ft) below. The Cenote Sagrado was a place of pilgrimage for ancient Maya people who, according to ethnohistoric sources, would conduct sacrifices during times of drought. Archaeological investigations support this as thousands of objects have been removed from the bottom of the cenote, including material such as gold, carved jade, copal, pottery, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, cloth, as well as skeletons of children and men.

Group of a Thousand Columns

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system. The columns are in three distinct sections: a west group, that extends the lines of the front of the Temple of Warriors; a north group, which runs along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in bas-relief; and a northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, which contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 metres (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages. A section of the upper façade with a motif of x’s and o’s is displayed in front of the structure. The Temple of the Small Tables which is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson’s Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil ), a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

El Mercado

This square structure anchors the southern end of the Temple of Warriors complex. It is so named for the shelf of stone that surrounds a large gallery and patio that early explorers theorized was used to display wares as in a marketplace. Today, archaeologists believe that its purpose was more ceremonial than commerce.

Osario

The Osario itself, like El Castillo, is a step-pyramid temple dominating its platform, only on a smaller scale. Like its larger neighbor, it has four sides with staircases on each side. There is a temple on top, but unlike El Castillo, at the center is an opening into the pyramid which leads to a natural cave 12 metres (39 ft) below. Edward H. Thompson excavated this cave in the late 19th century, and because he found several skeletons and artifacts such as jade beads, he named the structure The High Priests' Temple. Archaeologists today believe the structure was neither a tomb nor that the personages buried in it were priests.

The Temple of Xtoloc is a recently restored temple outside the Osario Platform is. It overlooks the other large cenote at Chichen Itza, named after the Maya word for iguana, "Xtoloc." The temple contains a series of pilasters carved with images of people, as well as representations of plants, birds and mythological scenes.

Between the Xtoloc temple and the Osario are several aligned structures: The Platform of Venus (which is similar in design to the structure of the same name next to El Castillo), the Platform of the Tombs, and a small, round structure that is unnamed. These three structures were constructed in a row extending from the Osario. Beyond them the Osario platform terminates in a wall, which contains an opening to a sacbe that runs several hundred feet to the Xtoloc temple.

South of the Osario, at the boundary of the platform, there are two small buildings that archaeologists believe were residences for important personages. These have been named as the House of the Metates and the House of the Mestizas.

South of the Osario Group is another small platform that has several structures that are among the oldest in the Chichen Itza archaeological zone.

The Casa Colorada (Spanish for "Red House"), is one of the best preserved buildings at Chichen Itza. Its Maya name is Chichanchob, which according to INAH may mean "small holes". In one chamber there are extensive carved hieroglyphs that mention rulers of Chichen Itza and possibly of the nearby city of Ek Balam, and contain a Maya date inscribed which correlates to 869 AD, one of the oldest such dates found in all of Chichen Itza.

In 2009, INAH restored a small ball court that adjoined the back wall of the Casa Colorada While the Casa Colorada is in a good state of preservation, other buildings in the group, with one exception, are decrepit mounds. One building is half standing, named Casa del Venado (House of the Deer). The origin of the name is unknown, as there are no representations of deer or other animals on the building.

Las Monjas

Las Monjas is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is a complex of Terminal Classic buildings constructed in the Puuc architectural style. The Spanish named this complex Las Monjas ("The Nuns" or "The Nunnery") but it was actually a governmental palace. Just to the east is a small temple (known as the La Iglesia, "The Church") decorated with elaborate masks.

The Las Monjas group is distinguished by its concentration of hieroglyphic texts dating to the Late to Terminal Classic. These texts frequently mention a ruler by the name of Kakupakal.

El Caracol ("The Snail") is located to the north of Las Monjas. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya practice), is theorized to have been a proto-observatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.

Akab Dzib is located to the east of the Caracol. The name means, in Yucatec Mayan, "Dark Writing"; "dark" in the sense of "mysterious". An earlier name of the building, according to a translation of glyphs in the Casa Colorada, is Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers,” and it was the home of the administrator of Chichén Itzá, kokom Yahawal Cho' K’ak’. INAH completed a restoration of the building in 2007. It is relatively short, only 6 metres (20 ft) high, and is 50 metres (160 ft) in length and 15 metres (49 ft) wide. The long, western-facing façade has seven doorways. The eastern façade has only four doorways, broken by a large staircase that leads to the roof. This apparently was the front of the structure, and looks out over what is today a steep, but dry, cenote. The southern end of the building has one entrance. The door opens into a small chamber and on the opposite wall is another doorway, above which on the lintel are intricately carved glyphs—the “mysterious” or “obscure” writing that gives the building its name today. Under the lintel in the door jamb is another carved panel of a seated figure surrounded by more glyphs. Inside one of the chambers, near the ceiling, is a painted hand print.